Beyond Translation and Judgment

My Gay Father’s Devotion to Faith and a Daughter’s Quest for Inclusive Christianity

My childhood was often very confusing, especially from a religious perspective. When my dad left my mom, she took it hard. I suppose I would too if my husband came to me right after our second child was born and said, “Oh, by the way, I’m gay.” But the ’80s were a different time. My father, like many gay men in those days, felt pressured to conform to society’s standards. He probably could have timed it a little better—and at least waited until her postpartum depression ended—but at some point, living a lie had taken its toll on him. I imagine that after enough time, it would break anyone.

I will never forget the agony I experienced as a child, torn between my extremely conservative mother and my gay father. When I was twelve years old, I overheard my mom arguing with my dad on the phone. She was upset that he wanted to take me camping, without her. Though I can’t recall the exact words, I clearly remember her saying he was “hellbound” and that she would be damned if she let him “drag me down with him.” I couldn’t understand why he—who spoke of his love for Jesus—wouldn’t go to Heaven, nor could I comprehend how my mother could be so certain about it.

The conflict came to a head that summer in a custody battle. My mom returned from court and instructed me to write a letter to my dad, telling him that I no longer wanted to see him because he was gay. I cried, telling her that wasn’t true, but she insisted. If I didn’t comply, she said he’d take me away, and I would never see her, my little brother, or my friends again. So, with tears streaming down my face, I wrote the letter, following her instructions carefully, thinking it would be the hardest thing I’d ever do. I was wrong.

The next day, my mother came home from court again and told me the letter wasn’t enough. The judge told her dad needed to hear me say those words aloud. Sobbing, I begged her not to make me do it. But she reminded me that he was planning to take me away forever. What she didn’t tell me was that my father only had a few months left to live. I knew he had AIDS, but at the time, I didn’t fully grasp how sick he was. We lived on opposite sides of the country and could only speak on the phone. When I asked him about his illness, he downplayed it, assuring me he had medication keeping him healthy. The 90s were a time when AIDS was rarely discussed, especially not with children.

“I will dial.” She instructed as if that made it any better. Eventually, my mother pressured me until I broke. I barely managed to say the words, “I don’t want to talk to you anymore,” before he hung up. Those were the last words I ever spoke to him. I believe she apologized for making me do it, but it wasn't enough for me. I didn't yet know that he was about to die and yet I was already grieving his loss. I cried myself to sleep, knowing that the chance for reconciliation had slipped away. My father died on my thirteenth birthday.

The hole left in my heart wasn’t just grief—it was guilt, shame, and self-loathing. There was no real goodbye, no chance to tell him how much I loved him or that I never viewed him the way my mother did. The brokenness lingered for years, despite twenty years of therapy. Though now, I understand that I was just a child. In my mind, I know I don't have to carry the guilt, but it scarred my heart so deeply, that I can still feel it; the echoes of a hollow little girl, trapped within me.

I tried to have a happy childhood and I realize there were bright spots but it’s the sadness that has stuck with me the most. I tried to have a healthy relationship with my mom. I love her and wish things were different, but her harsh judgment has only increased over the years. Despite offering her countless chances, despite numerous conversations about boundaries and not saying unkind things about marginalized people in front of my children, these things have never improved. In her mind, she is “saving” my kids from the devil. Because verbal boundaries never worked, the only thing that has helped is to keep our contact with her to a minimum. This breaks my heart but I can't let my kids grow up with that kind of confusion. I want them to know only love.

In addition to losing trust in my mother, This experience also marked the time when I began questioning my faith. Its ironic that what she saw as making me a better Christian only managed to put a wedge between myself and God. But in the back of my mind, I didn’t want to let go of my Faith because my hope is that I will see my dad again in Heaven and can finally make things right.

Two people helped me begin to reframe my relationship with God. One was my boss, who had a deep, nonjudgmental faith. Her approach was grounded in love and acceptance, not condemnation. The other was a pastor at the Presbyterian church I began attending when my son was little. I shared my struggles with him, and he explained that many interpretations of the Bible, especially those condemning homosexuality, actually defy the teachings of Jesus. He reminded me that Christianity, in its true essence, was rooted in love.

So why do so many Christians view homosexuality as a sin? Much of the misunderstanding stems from biblical passages that have been taken out of context. The passages from Leviticus, Romans, and Corinthians are often cited to condemn homosexuality. But are these interpretations accurate?

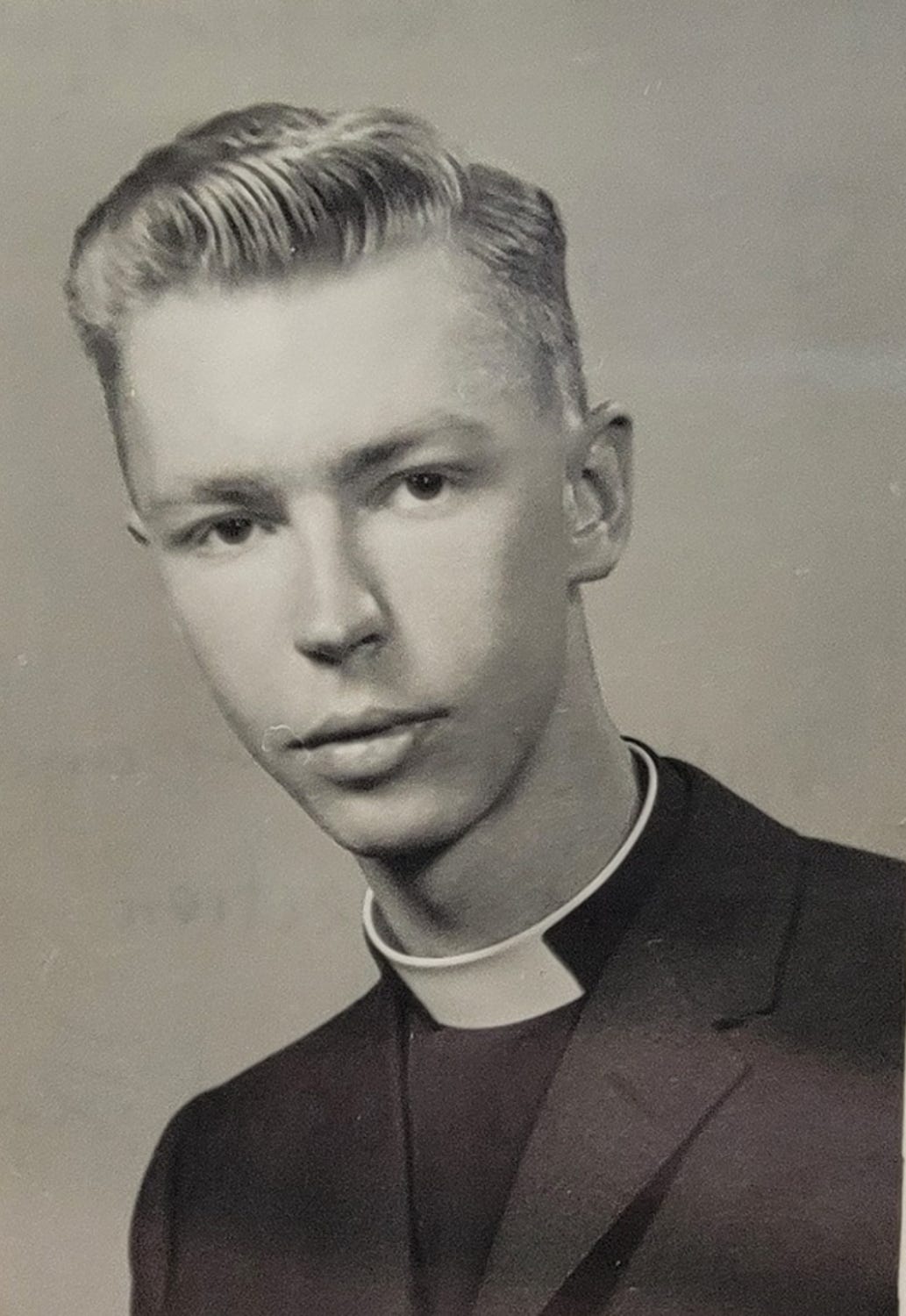

In 1959, a young seminary student, David Fearon, discovered the root of this prejudice. Fearon wrote a letter to Dr. Luther Weigle, one of the translators of the Revised Standard Version (RSV), warning about a mistranslation that was becoming a “sacred weapon” for those who took every word of the Bible literally. Fearon, highly knowledgeable in ancient Greek, was concerned about a passage that was being misinterpreted.

The issue lay in the term “homosexual.” In I Corinthians, Paul used a compound word—arsenokoitai—that didn’t exist before. It was a combination of two Greek words meaning “man” and “bed.” The problem was, that this word wasn’t properly understood at the time. There were other words for homosexuality, but Paul didn’t use them. Fearon believed that this mistranslation was used to justify discrimination against people who were attracted to the same gender.

Further research revealed that the term Paul used referred to abusive sexual practices, not consensual homosexual relationships. At the time, the city of Corinth was a major port, and many sailors engaged in prostitution with young boys—acts that were violent and exploitative. These practices were what Paul was condemning, not the loving relationships that we know today.

In Leviticus, the prohibition against same-sex acts is tied to health concerns. In an era where diseases like leprosy were rampant, the concern was about the spread of disease from promiscuity, not the relationship itself. If these verses were referring to those who were in monogamous, same-sex relationships, there would have been no reason for concern.

Paul’s use of arsenokoitai in I Corinthians and I Timothy connects these actions to pagan temple rituals, which often involved the abuse of children. He was condemning the exploitation and violence, not same-sex relationships. Unfortunately, the mistranslation of this word spread throughout Bible translations in the 20th century, with the term “homosexual” becoming entrenched in Christian doctrine, despite the inaccuracy of the original text.

This mistranslation was so widespread that by 1971, even after some revisions were made to future editions of the RSV, the damage had been done. Many Bible translations that followed continued to use the inaccurate term. As a result, generations of Christians have been taught to condemn homosexuality without understanding the true meaning of these scriptures.

However many theologians believe that the Bible’s central message is one of love, not exclusion. The overarching theme throughout scripture is to love one another. Jesus’ parables, such as the story of the Good Samaritan, teach us to love our neighbors, regardless of their background or differences. The Prodigal Son shows us that forgiveness is always available, no matter how far we’ve fallen. In the Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, Jesus emphasizes that it is the humble, not the self-righteous, who are favored by God.

When we look at the totality of Jesus’ message, it becomes clear that condemning LGBTQ+ individuals goes against the very heart of the Gospel. The hypocrisy of some Christian communities, which overlook sins like gossip, greed, and divorce while condemning homosexuality, reveals the selective morality that underpins this prejudice.

The psychological harm caused by the church’s teachings on homosexuality is profound. LGBTQ+ individuals are often driven away from faith communities and made to feel unloved and unwelcome. This goes against the core Christian message of love and acceptance. In a faith that teaches love as the most important virtue, it is heartbreaking that LGBTQ+ people are often rejected, isolated, and made to feel shame for simply being who they are.

My faith has evolved. I still believe in God, but my faith is now one that seeks understanding and strives to love unconditionally. I believe in a God who sees beyond labels, who welcomes all people and calls us to do the same.

It’s striking that the way God is described in the Bible is similar to how scientists describe the universe. Both are infinite, encompassing everything that has ever been or will be. Perhaps God is a metaphor for the vastness of the universe, and understanding the Bible requires us to distinguish between what is literal and what is symbolic.

In a universe so vast and beyond human comprehension, who are we to tell others who they can or cannot love? I Corinthians 13:2 reminds us that “if I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries, but do not have love, I am nothing.” This powerful message tells us that love is the highest virtue. If we have love, we embody God’s will, and this should extend to everyone, regardless of their identity or orientation.

God’s command to love one another is central to the Christian faith. If we fail to act with love, we are missing the entire point. The hypocrisy of condemning others for being different, while ignoring our own failings, is what leads to the suffering of so many people—especially those in the LGBTQ+ community.

Christianity was never meant to be treated as an exclusive club. If you knew nothing of Jesus’ teachings and some Christians made you feel unwelcome in church, excluded you, and lowered your sense of self-worth, would you think favorably of Christians? Probably not. Over time, would that grow the church? No. Does a lack of inclusion within the church (or anywhere) unite or divide us? It’s created a ripple effect so vast that if we don’t drastically change how we treat others, the Christian faith, as Christ intended, will face extinction. Some may not care, certain they are right, but what will your excuse be on judgment day if asked why you didn’t put love into action? Why did you teach your children it was acceptable to demean someone for being different? What if this led to their depression, self-loathing, or even suicide? Why didn’t you stand up for your Black neighbor who was treated unfairly because of his ethnicity? Why didn’t you do more to help the poor? Why did you tell immigrants they were unwelcome in your country? Or even if you didn't outwardly exclude, why did you vote for leaders who supported this? How are you prepared to answer those questions?

I’m merely playing devil’s advocate, here but if I am wrong, and God asks me why I held these views, I can answer with a clear conscience. I did my best to live according to the teachings of Jesus, by loving others and treating them with kindness and compassion. I firmly believe that God does not create some people to be excluded from His love. His house should be open to all.

In the end, it is love that matters. The hypocrisy that is poisoning Christianity must be addressed and rectified. Inclusion is morality. I stand firm, and I will die on this hill.

In the following Video, Rev. David shares his story of the letter that is bringing hope and inclusion into the Church.

You can also support my writing through “Buy Me A Coffee”

Yes! It took me so long to fully grasp that concept. I’ve been in therapy for nearly 2 decades and it probably took close to a decade for that to sink in; for me to realize that all the reasoning and explaining in the world was never going to change her mind.💔

I am sorry for you enduring abuse as a child, and I simultaneously rejoice in you, not only as a survivor, but as one able and willing to include us in your journey of recovery. I am 74 years old, an ordained pastor leading a church, the father of four, author of ten books, etc. and am still recovering from having been raised in hell by parents who, today, would have been placed in prison. My addiction to alcohol and other drugs, is now decades dormant thanks to programs of recovery. There was no religion in the family whatsoever. Any yet, somehow, and perhaps perversely so - I inherited strength, determination, and immense resilience from my bout with childhood. And I learned compassion and advocacy on behalf of those who needlessly and unjustly suffer many of the indignities of life. Your suffering has wounded and outraged my soul, and also rendered my heart more vulnerable and strong. We are wounded warriors, battle tested, who have turned toward light and peace. Keep on writing. I thank the God of my understanding for your blessings. Peace, Rev. Dwight Lee Wolter.